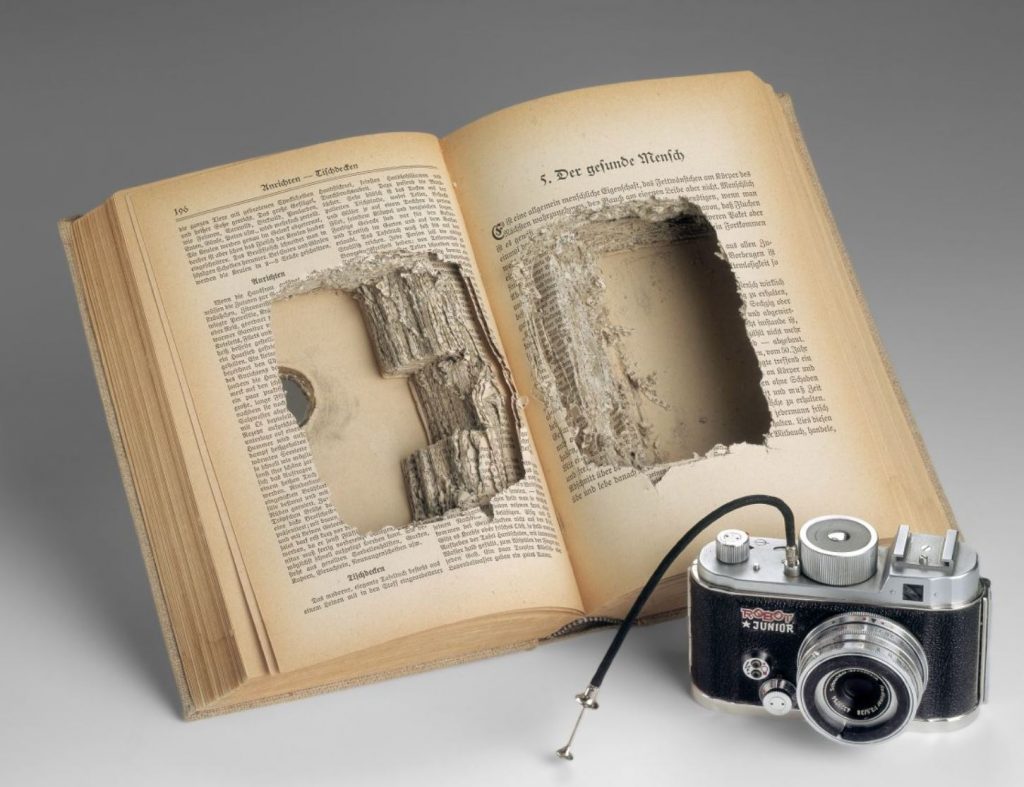

A German watchmaker designing a camera. Is that even possible? Agfa and Kodak did not believe in Heinz Kilfitt’s groundbreaking design, a camera with a heavy spring that could be like a watch wound up and automatically operate both the film and the shutter. Only the Otto Berning optic company saw something in the strange-looking, futuristic camera in 1934 and took the patent and called it the Robot. The beginning of a success series.

I was immediately impressed by the strange little camera. Heavy and striking with that big spring in the middle on the camera. A glittering camera made entirely of metal with a small Schneider Kreuznach wide-angle lens. But when you start to turn up the spring as if by itself and operate the shutter button, the magic of the Robot’s miniature world opens up before you.

They call it the hallmark spring motor, a unique spring mechanism that can shoot 4 frames per second (!), winds the film and keeps the shutter cocked. Fully mechanical and that almost ninety years ago. Only Leica managed to develop a similar motor (Mooly) in 1938 that could be placed as an add-on under the III series, with 2 frames per second and a maximum of 12 pictures. The Robot could shoot as many as 24 pictures on one full “spring tension” (some versions had even a double-wind motor which could expose 50 frames). But the Robot used a different, smaller film format, a square 24×24 mm. When the Robot was introduced, Berning also used its own unique films and cartridges before finally switching to Kodak’s 135 in 1951. So be aware that old Robot’s require special re-loadable film canisters, type N cartridge. You first have to respool 135 film into that canister. The models from the fifties onwards take modern 135 film.

I myself have a 1954 Robot Junior Star (with many senior qualities!) which is derived from the larger Robot Star. Remarkably, this one, and many of the Robot cameras do not have a rewind button! So you either have to develop the film yourself in a dark room or make sure you get the original take-up cannister back when sending it in. The button on the top right of the camera is only for tightly inserting the film. The film insertion itself seems complicated because the take-up spool consists of three parts, an outer and inner sleeve and the take-up spool. The film is pinched on the little take-up spool behind a small plate with the first perforation hole of the film. Then first reinsert the inner and outer sleeve and then the 135 filmcassette together with the whole take up cannister can be put back into the camera. With the small knob on the camera body make sure the film moves tightly over the small gear. After that you wind the main spring two times and fire it. Now you are at number one that can be manually set on the frame counter by pushing the tiny button on the top front and simultaneously turn the frame number ring.

Taking photos is a great convenience with the Robot. Several interchangeable lenses are available. Initially Zeiss Tessars were used, but later Schneider-Kreuznach became the main supplier for the 26 mm screw mount. The standard lens was the Radionar or Xenar wide-angle (30, 38 or 40 mm). As a telephoto lens, there was the Tele-Xenar 75 mm or the famous Zeiss Sonnar that also existed for Robot. There were F3.5 versions, but also very fast F1.9 ones. Later 150 and 200mm lenses were added and also zoom lenses, as Kilfitt was after all also the inventor of the very first (Voigtlander) zoom(ar) lens. The Robot Junior has a small focus screen and distances must be estimated. There is also no exposure meter. But for orderly success, unique color combinations were applied to the lens so that the user could use ‘color coding’ to master default settings. These quick shots used green as shutter speed and aperture for distances up to 5 meters, yellow up to 10 meters and red up to 20 meters and infinity. The colors also served as exposure meter, green for full sunlight and red, for example, in dark weather. The ring also indicated the distances within a sharp picture could be achieved given a certain aperture. The shutter provided times up to 1/500s and can be adjusted with the fancy small wheel next to the lens.

The camera is amazingly well designed in many ways. Some will find it all just strange, but those who really want something different, this is it! The quality of the camera is very good, also the lens produces very sharp pictures especially at smaller apertures. The camera has an accessory shoe for a flash (or uncoupled rangefinder/lightmeter) that can be connected to the PC sync contacts on the front (both for M flash bulbs and X electronic flash units, synced to 1/50 with bulbs and 1/500s electronically). Finally, the camera has a shutter lock button.

The Robot was particularly popular with the German Air Force in World War II. Pilots could take serial shots automatically from the plane with one hand. The silent shutter also ensured that the Robot gained name and fame as a spy camera in the Cold War. With the Robot, you have a unique piece of history in your hands. A must for every collector. I was able to discover twelve different models, so that seems plenty of choice. Next to the Junior, the rangefinder versions are the most popular, but harder to come by. The expensive Robot was not affordable for everyone and appeared in smaller numbers, so be quick while they are still around.